Last September, Leah Penniman, a food sovereignty activist and author of Farming While Black, gave a talk at Harvard Divinity School on “African Diasporic Wisdom for Farming and Food Justice.” In it, she reportedly told the story of her great, great grandmother. About to be kidnapped from her home in West Africa, she made a “really audacious and courageous decision” to gather the seeds of okra and other crops and braid them into her hair.

“They knew that wherever they were going,” Penniman explained, “they believed there would be a future of tilling and reaping on the soil, and there would be some seed we all needed to inherit. That’s what our grandmothers did for us.”

In so many ways, okra is the vegetable for the moment.

A person’s reaction to it — and relationship to it — speaks volumes about their identity.

“Okra is the food of my ancestors, who were pulled from their homes in Africa,” writes Kayla Stewart in an essay recently published on Medium. “It was grown by those enslaved along the Carolinas, and devoured by them in Louisiana. Okra is a constant in my familial story — one that includes deep memories and gaping holes of history.”

Ask a white person about okra, and you’ll likely get something a good deal less deep — maybe “I like it, as long as it’s not slimy.”

Because it is so important in Black American cooking, and also shows up in cuisines from around the world, it’s hard to think of an ingredient that’s more ideally suited as a place for Americans of all cultures to meet — especially anyone who strives for deeper understanding of Black foodways.

“People tend either to love or hate okra, which originated in Africa and spread to Arabia, Europe, the Caribbean, Brazil, India, and the United States,” wrote chef Marcus Samuelsson in his 2007 cookbook Discovery of a Continent: Foods, Flavors, and Inspirations from Africa. “I happen to love it and think it adds great texture and color to meals, but I do remember being a little put off by its slimy texture the first time I had it. Once you get over that, it’s easy to like.”

With that, he offers a simple and delicious recipe for a quick Spicy Okra sauté, with tomatoes, red onions, chiles, garlic and peanuts.

Marcus Samuelsson’s Spicy Okra, from his 2007 cookbook ‘Discovery of a Continent: Foods, Flavors, and Inspirations from Africa’

As its peak season is late summer and early fall, it’s a great time of year to celebrate okra — which continues growing until the first frost. (In case you’re wondering, Texas is the top okra-producing state in the U.S., followed by Georgia, California and Florida.)

This time of year I love to char it on the stovetop grill, toss it in something spicy and serve it as a nibble with cocktails. You don’t really need a recipe for that — just cut each okra in half lengthways, toss them in a little olive oil and salt, and grill them, cut-side down first, till they’re a little charred. Add something spicy — maybe sambal oelek, the Indonesian chile paste, or lightly spicy Aleppo pepper — toss, and serve. Sumac would be great, too.

Okra dishes, of course, are found throughout Africa. “The mucilaginous pod is the continent’s culinary totem,” wrote Jessica B. Harris in her seminal 1998 book, The Africa Cookbook:Tastes of a Continent. “From the bamia of Egypt to the soupikandia of Senegal, passing by the various sauces gombos and more, this pod is used in virtual continent-wide totality. It is native to Africa, and its origins are trumpeted by its names in a number of languages throughout the world. The American okra comes from the twi of Ghana, while the French opt for gombo, which harks back to the Bantu languages of the southern segment of the continent.”

Shrimp gumbo with smoked andouille sausage and okra, served with rice

So yes — it also gives gumbo, Louisiana’s iconic dish — its name.

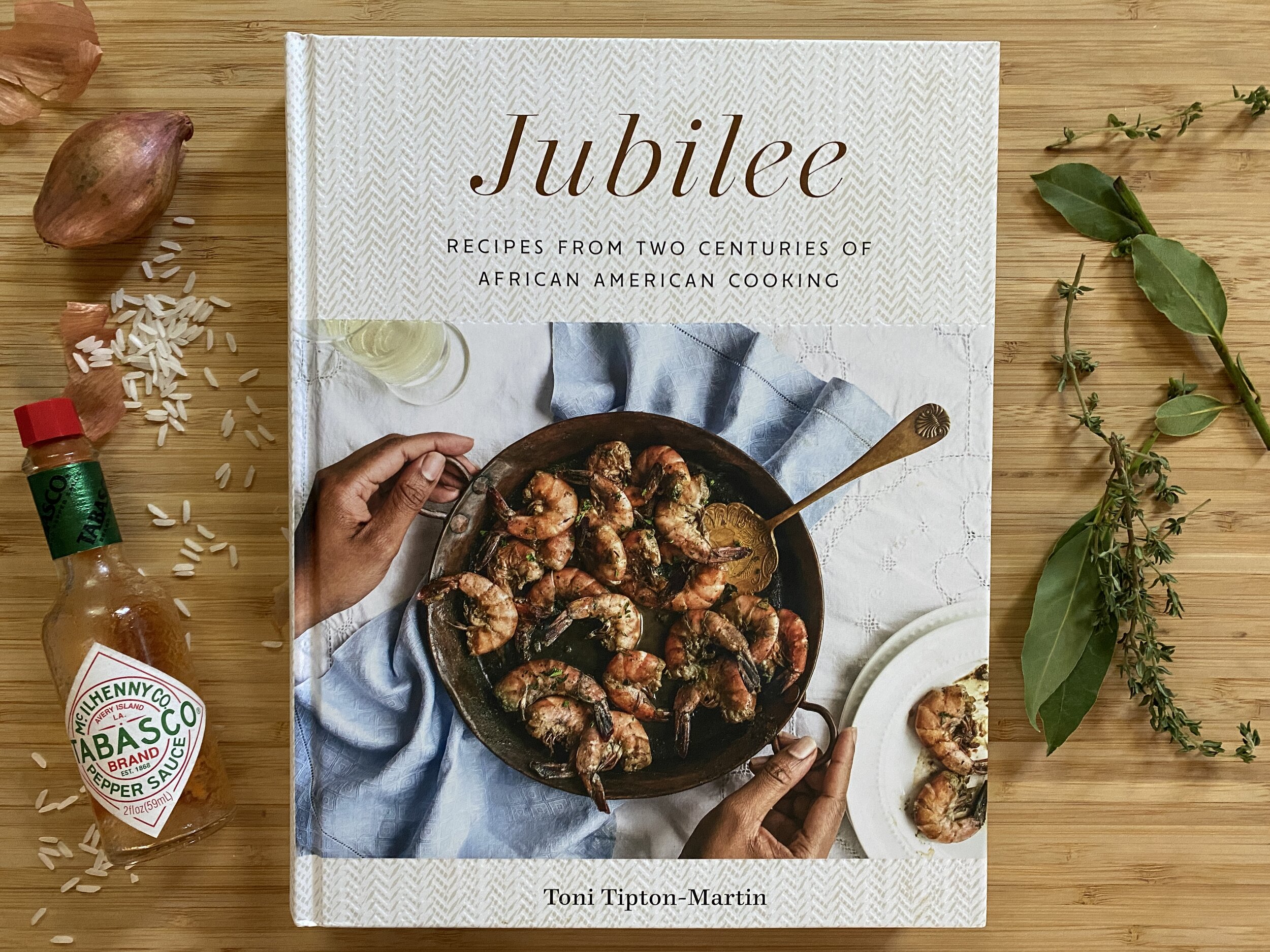

In Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking, Toni Tipton-Martin points out that “Ochra” Gumbo was Recipe Number 44 in What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, published in 1881 by Abby Fisher. “Her formula,” writes Tipton-Martin, “which involved boiling a beef shank to create a savory and alluring broth, survived through the ages, the recipe variously being called okra stew, okra soup and okra gumbo.” She reproduces Mrs. Fisher’s recipe, which is short and sweet:

“Get a beef shank, have it cracked and put to boil in one gallon of water. Boil to half a gallon, then strain and put back on fire. Cut ochra in small pieces and put in soup; don’t put in any ends of ochra. Season with salt and pepper while cooking. Stir it occasionally to keep it from burning. To be sent to the table with dry boiled rice.”

During the first part of okra’s long season, in early pandemic, I found okra, shrimp and andouille sausage at the supermarket all at the same time, and happened to have a package of dried shrimp in my larder, so I improvised a gumbo. It was deliciously soothing — both to make and to eat. I made it again, and again, tweaking until it was just where I wanted it.

Try our recipe as is, or tweak away: Gumbo is ideally suited to improvisation.

Many gumbos get their body from okra; others from roux or filé powder (Native American sassafras powder). This one gets its body from a roux cooked long and slow to a beautiful coffee-with-a-touch-of-milk color, and the okra — which I roast first, to pull out the stickiness — gets added at the end. I serve filé, along with Louisiana hot sauce, at the table.

And finally, one of our favorite ways to celebrate okra is pickling it. We usually find okra pickles a bit sweet for our taste, but a recipe in Sweet Home Cafe Cookbook, the 2018 volume featuring recipes from the restaurant at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. is perfectly marvelous.

The okra pods stay crunchy and snappy, and the pickles — brined with turmeric, garlic, coriander and Thai chiles — are delightfully spicy and bright.