By Leslie Brenner

[This article was originally published, in slightly different form, on Feb. 8, 2024.]

With Lunar New Year right around the bend — New Year’s Eve is Tuesday, Jan. 28 — you may be planning a celebratory feast. And of course the 15-day spring festival that begins on New Year’s Day, Jan. 29 is a great time to focus on Chinese cooking.

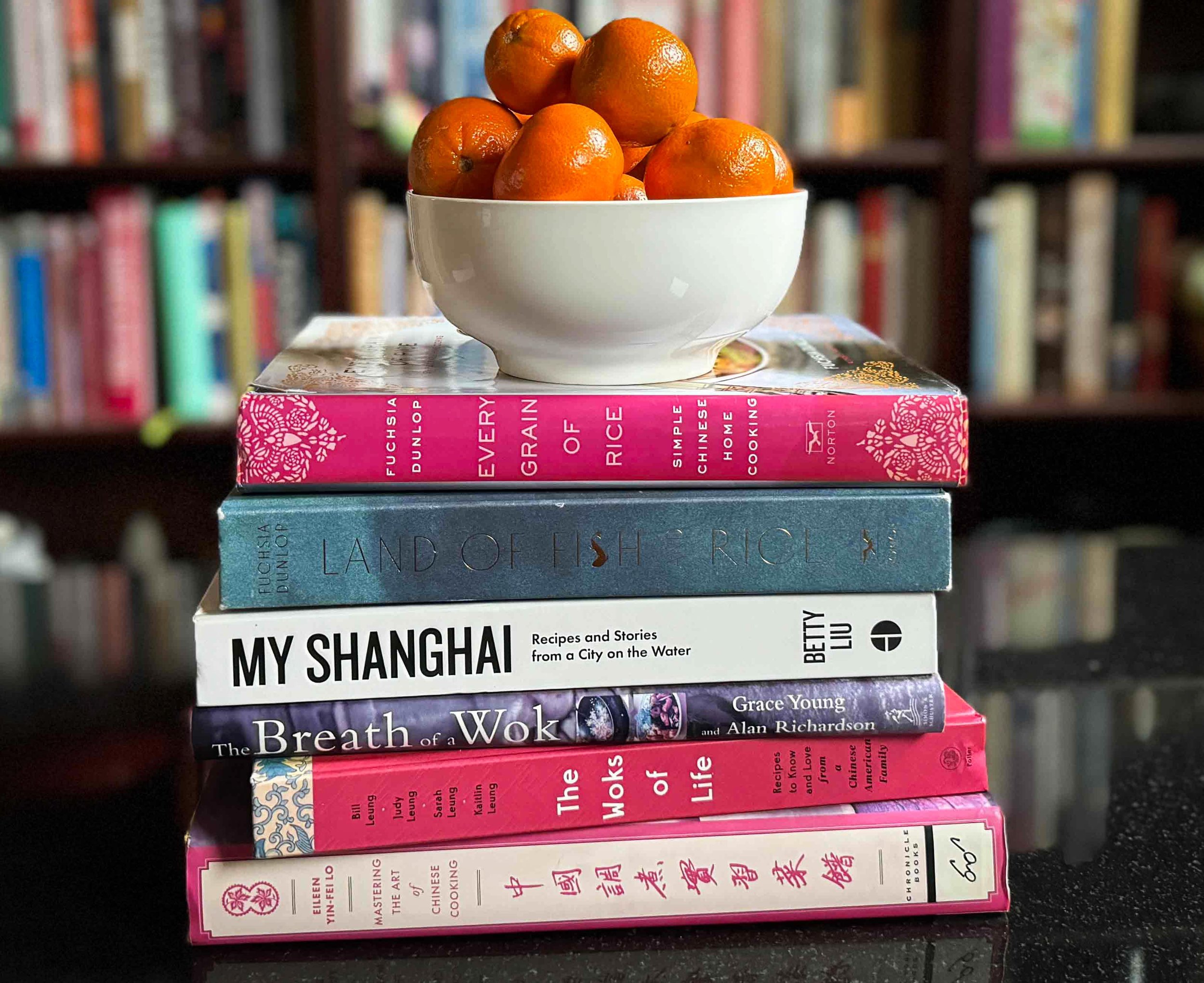

We’ve rounded up our favorite Chinese cookbooks to serve as inspiration and guide you with great technique — with a selection of recipes from them that are perfect for the holiday season.

The Breath of a Wok

Grace Young's award-winning 2004 book approaches cooking as a poet might, looking deeply into the soul of the cuisine. For Young, it all starts with the wok, and she walks readers through everything about it, from how to choose one to purchase, to "opening" the wok, to seasoning it with dishes early in its life. She then teaches us to stir-fry with wok hay — that ineffable "breath of a wok" that distinguishes the best Chinese cooking.

The book is extremely useful if you’re cooking for Lunar New Year, as it includes — buried way back in the index — a list of 66 recipes appropriate for the holiday.

There’s also a helpful section about New Year’s menus, with four suggested menus — all of which are made up of dishes that can be made in advance. The lead-off recipe is Jean Yueh’s Shanghai-Style Shrimp, which is auspicious because shrimp represent happiness. Sweet and savory, with ginger and scallions, it’s also quick and easy.

RECIPE: Jean Yueh’s Shanghai-Style Shrimp

The Breath of a Wok, by Grace Young and Alan Richardson, 2004, Simon & Schuster, $38.50

Mastering the Art of Chinese Cooking

The books of trail-blazing author Eileen Yin-Fei Lo, who died in late 2022, were my first teaching manuals when I began exploring Chinese cooking 17 years ago. Mastering the Art of Chinese Cooking, which was published in 2009, is structured like a Chinese cooking school — as a series of lessons, all centered around the Chinese market. With more than 150 recipes and beautiful photos throughout, it's a classic.

It includes a chapter called “Creating Menus in the Chinese Manner,” in which there’s a wonderful page outlining a Lunar New Year banquet.

Among the New Year’s dishes are Clams Stir-Fried with Black Beans, auspicious because “When clams open, they symbolize prosperity.”

RECIPE: Clams Stir-Fried with Black Beans

Mastering the Art of Chinese Cooking by Eileen Yin-Fei Lo, photographs by susie cushner, 2009, Chronicle Books

Every Grain of Rice

If you could purchase only one Chinese cookbook, this would be my recommendation. Author Fuchsia Dunlop, who was the first Westerner to train as a chef at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine in Central China, is a wonderful teacher. Her well selected recipes have always worked brilliantly for me (she’s a careful writer, and the book is well edited); she has a terrific palate, so everything’s delicious. You’ll pick up lots of sound technique along the way. [Read our review.]

In fact, all of Dunlop’s books are outstanding — including The Land of Fish and Rice; The Food of Sichuan and her latest title — which is not a cookbook — Invitation to a Banquet.

For New Year’s, try the Every Grain of Rice’s Yangzhou Fried Rice.

RECIPE: Yangzhou Fried Rice

EVERY GRAIN OF RICE: SIMPLE CHINESE HOME COOKING, BY FUCHSIA DUNLOP, PHOTOGRAPHS BY CHRIS TERRY, 2012, W.W. NORTON & CO., $35.

The Woks of Life

Fun, approachable, relatable and highly user-friendly, the cookbook spun out of the Leung Family’s popular cooking website is another great primer. A whole fish is a must for Chinese New Year feasts, and The Woks of Life’s Cantonese Steamed Fish — with ginger, scallions, cilantro and soy sauce — is a great choice. [Read our review of the book.]

RECIPE: Cantonese Steamed Fish

There’s also a splendid recipe for jiaozi (dumplings), which are traditionally enjoyed in the north of China for New Year’s. They’re filled with pork, mushroom and cabbage.

RECIPE: Woks of Life Pork, Cabbage and Mushroom Dumplings

THE WOKS OF LIFE: RECIPES TO KNOW AND LOVE FROM A CHINESE AMERICAN FAMILY BY BILL, JUDY, SARAH AND KAITLIN LEUNG, CLARKSON POTTER, $35

The Vegan Chinese Kitchen

This 2022 book from Hannah Che, creator of the excellent blog The Plant-Based Wok, is inspiring and beautiful — and a real gift for vegans and vegetarian.

Now based in Portland, Oregon, Che studied in Guangzhou, at the only vegetarian cooking school in China. There she immersed herself in zhai cai, the plant-based cuisine with centuries-old Buddhist roots that emphasizes umami-rich ingredients.

Leafy greens symbolize wealth, and Che’s Blanched Lettuce with Ginger Sauce is deliciously auspicious for the holiday. [Read our review of the book.]

RECIPE: Hannah Che’s Blanched Lettuce with Ginger Sauce

THE VEGAN CHINESE KITCHEN: RECIPES AND MODERN STORIES FROM A THOUSAND-YEAR-OLD TRADITION, BY HANNAH CHE, CLARKSON POTTER, 2022, $35

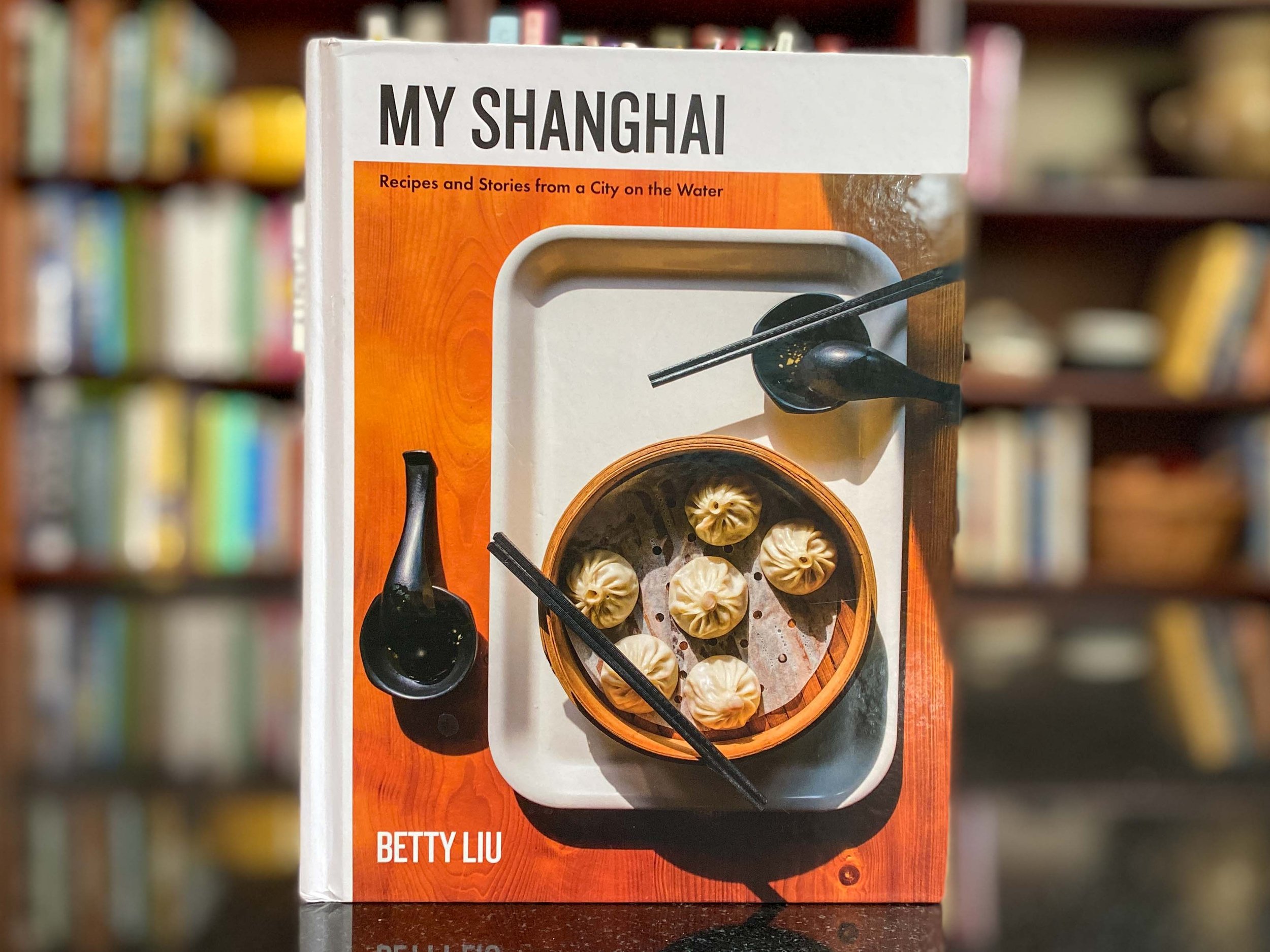

My Shanghai

Betty Liu has a lovely page about Lunar New Year in her 2020 book, My Shanghai, which we wrote about two years ago.

Pork dishes are big for the holiday, and you can’t do better than Liu’s Shanghai-style red-braised pork belly.

RECIPE: Betty Liu’s Mom’s Shanghai Red-Braised Pork Belly

My Shanghai: Recipes and Stories from a City on the Water, by Betty Liu, 2020, Harper Design, $35

EXPLORE: All Cooks Without Borders Chinese Recipes