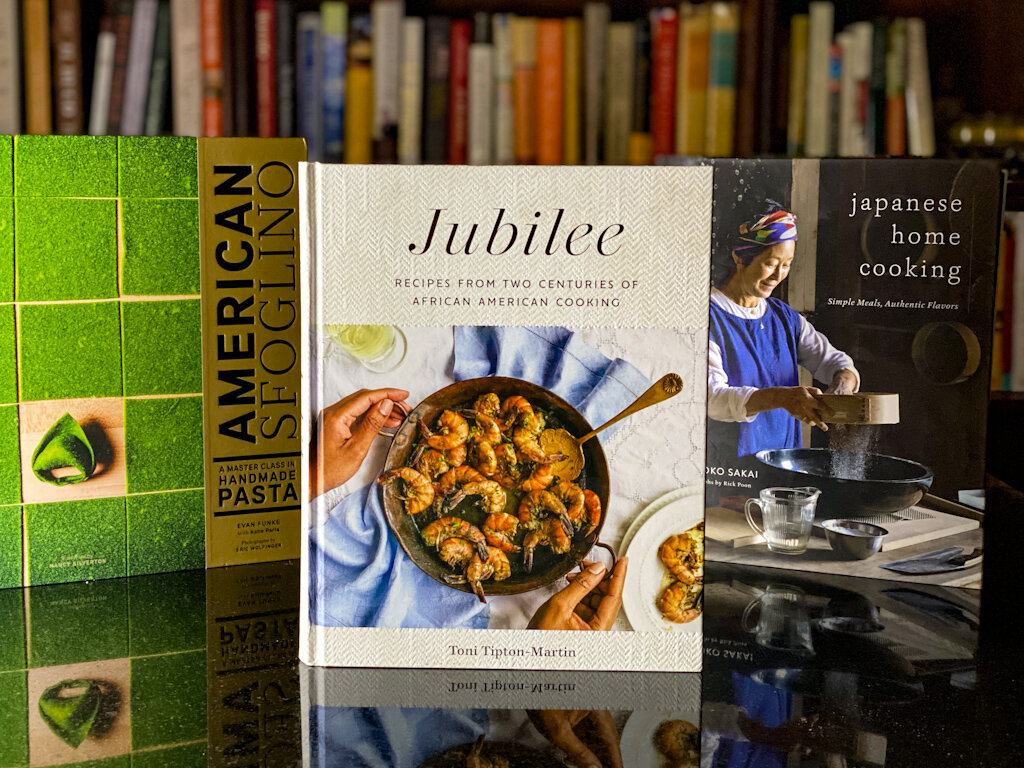

The International Association of Culinary Professionals announced the winners of its 2020 Book Awards on Saturday, including its prestigious Cookbook Awards.

Toni Tipton-Martin’s Jubilee: Recipes from Two Centuries of African American Cooking (Clarkson Potter) won the top prize, Book of the Year, as well as the award for best cookbook in the American category. Francis Lam was the editor.

In our June review, we called Jubilee “deliciously inspiring,” discussing and including recipes for Tipton-Martin’s Layered Garden Salad, Sautéed Greens and Country-Style Potato Salad. In an earlier story, we raved about her recipe for Pickled Shrimp — which is one of our favorite recipes of the year to date.

Pickled Shrimp from Toni Tipton-Martin’s ‘Jubilee’ is one of our favorite recipes published in 2020.

Sonoko Sakai’s Japanese Home Cooking: Simple Meals, Authentic Flavors (Roost Books) won the prize for best new cookbook in the International category. Sara Berchholz was the editor.

“If you are looking to dive (or tip-toe) into Japanese cooking and seeking one great book to guide you, you can do no better than this delightful volume,” we wrote in our review (also in June). We offered up Sakai’s recipes for Okonomiyaki, Cucumber Sunomono and Koji-Marinated Salmon as evidence.

Okonomiyaki from ‘Japanese Home Cooking’ by Sonoko Sakai

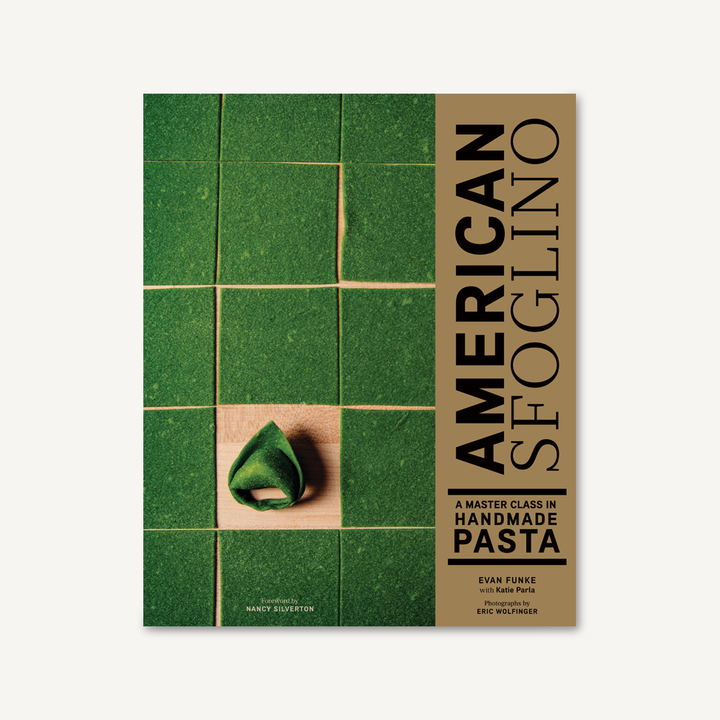

While we haven’t gotten around to reviewing American Sfoglino yet, we do have a story about it in the works, and taking a deep dive into Funke’s pasta-making technique has forever changed the way we’ll approach making pasta by hand. The book won in the Chefs & Restaurants category. A mini-review will be coming soon.

Other titles winning IACP top honors include Pastry Love: A Baker’s Journal of Favorite Recipes by Joanne Chang (Baking category); The Complete Baking Book for Young Chefs by the Editors at America’s Test Kitchen (Children, Youth & Family category); On the Hummus Route by Ariel Rosenthal, Orly Peli-Bronshtein and Dan Alexander (Culinary Travel category) and Milk Street: The New Rules: Recipes That Will Change the Way You Cook by Christopher Kimball (General category). Find a complete list of winners and finalists here.

Congratulations to all the IACP winners and finalists!