A few years back, when Cooks Without Borders was just a wee thing, I developed an obsession with okonomiyaki.

A thick, luscious savory Japanese pancake, okonomiyaki is filled with vegetables and seafood or meat, painted with an umami-rich okonomiyaki sauce or tonkatsu sauce, perhaps squiggled with mayonnaise and definitely topped with bonito flakes. The bonito flakes — katsuobushi in Japanese — are so thin and light that they catch air currents and wave around, looking like they’re alive.

There’s a bit of a cult in the U.S. around okonomiyaki. After I wrote a story about the crazy pancake for The Dallas Morning News (in 2016), I decided to find or develop a recipe for Cooks Without Borders.

Easier said than done! Too thick, too pasty, too gloppy, too weird — I couldn’t manage to get it right. Recipes were scarce, sketchy, flawed, and I was flailing developing my own. Unable to nail the batter, I resorted to buying something called “okonomiyaki flour” in a Japanese supermarket. The store-bought okonomiyaki sauce I was painting them with was cloyingly sweet. None of it was working.

After something like Okonomiyaki Number Twelve, Thierry begged for mercy. “Stop!” he cried. “Yamero, kudasai ! やめろください!”

Kidding. Thierry does not speak Japanese (nor do I).

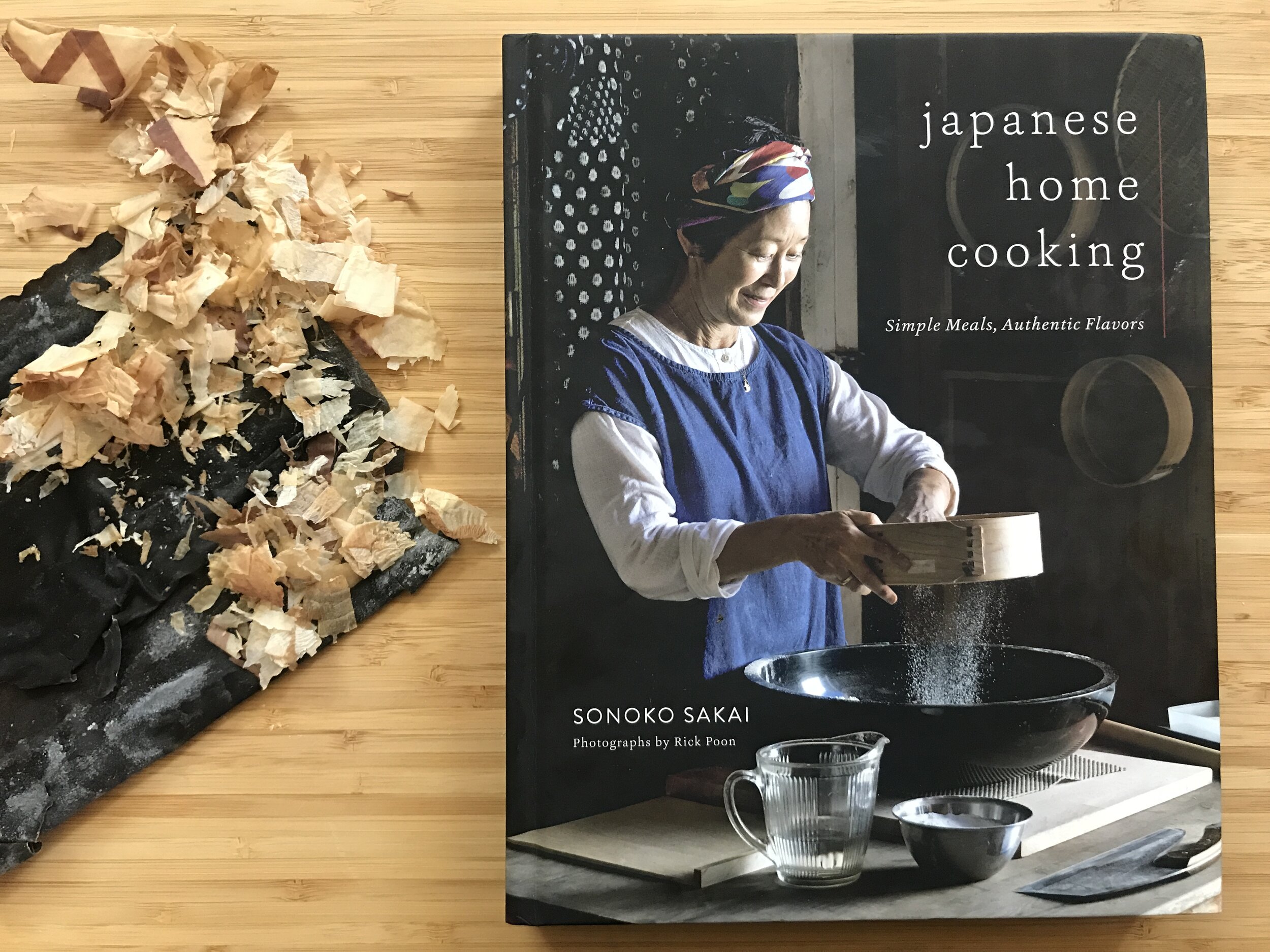

The point is, there is now a book that has an okonomiyaki recipe that works: Sonoko Sakai’s delightful Japanese Home Cooking: Simple Meals, Authentic Flavors.

Thanks to Sonoko Sakai’s Japanese Home Cooking, we can now make okonomiyaki at home.

Whether or not a wild-looking savory pancake speaks to you at all, if you are looking to dive (or tip-toe) into Japanese cooking and seeking one great book to guide you, you can do no better than this delightful volume. Published last November, it is now a finalist for a prestigious 2020 IACP Cookbook Award in the International category.

To so many of us, Japanese cuisine means high-flying restaurant food — the kind of precise and specialized dishes chefs spend years (or even decades) learning to execute. I’ve never wanted to make nigiri sushi at home, for instance, as it depends on sourcing the best and most interesting fish, treating them properly, having the knife mastery to slice them to their best advantage— oh, and getting the rice right, which is an elaborate subject in itself. Yakitori — skewered chicken — involves grilling the poultry over blazing-hot binchotan (Japanese charcoal), something I wouldn’t be able to manage at home, even if I could find the binchotan. Because the places I’ve lived — Los Angeles, New York, the San Francisco Bay Area and Dallas — all have such great Japanese food, I’ve always preferred to leave it to the pros.

However, going back to my childhood in L.A., I always loved another kind of Japanese cooking, something much closer to home cooking. It’s the kind of humble, approachable fare that Sakai features in Japanese Home Cooking.

You might start with something quick and easy, like a cucumber sunomono. One taste of the Sanbaizu dressing — mirin, rice vinegar and soy sauce simmered very briefly then cooled — and I was back at Tempura Hiyama, the beloved neighborhood mom-and-pop of my childhood in the San Fernando Valley.

Sakai’s cucumber sunomono with wakame seaweed is garnished with grated ginger and toasted sesame seeds.

Sakai adds wakame (the same seaweed that’s common in miso soup), along with glass noodles and grated ginger, but you could go even simpler with just the cukes, dressing and sesame.

If you want to go into Japanese cooking in any kind of depth, you’ll want to put dashi in your bag of tricks; not surprisingly, Sakai leads off her book with a chapter about it. A quick stock made from nothing more than katsuobushi (those same shaved bonito flakes that wave around on top of the okonomiyaki), kombu (a dried seaweed) and water, it is the basis for much of Japanese cooking — just as veal stock is the foundation, or fond in French, of French cooking, but it’s even more ubiquitous in Japanese dishes. Dashi is easily achieved — just heat a piece of kombu in water, remove it, and drop in a bunch of bonito flakes, let them steep for two minutes then strain them out.

Kombu (upper left), katsuobushi (lower left) and water combine to make dashi (right).

Miso soup with shimeji mushrooms, tofu, lemon zest and scallions

I like Sakai’s approach to it. She’s quick to let readers know that rather than discarding the spent kombu and bonito flakes, you can (and should) use them to make a secondary dashi. While the first one is good enough to sip on its own (and has lots of culinary uses), the secondary dashi is good for miso soup and for seasoning a wide variety of dishes. Miso soup, by the way, is super easy to make once you have dashi: Just stir in some miso and add whatever else you like — tofu, mushrooms, wakame seaweed, etc.

Sakai provides recipes for several other dashis as well, including two vegan versions (one using only kombu, and the other kombu and shiitakes). That’s a splendid solution for vegans who are limited to what they can eat in a Japanese restaurant: It’s super easy to make vegan miso soup at home.

Also useful is a section about shio koji — which is the easiest way for home cooks to get in on the koji craze that has captivated chefs. To prepare it, get your hands on rice koji — rice that has been innoculated with koji (you’ll find a link to purchase it in the recipe for Koji-Marinated Salmon below). Massage that together with salt and hot water, let it ferment 5 days and you’ve got a useful ingredient that you can use to rub into napa cabbage leaves to make a quick pickle, or onto meat, chicken, salmon or other fish as an overnight (or up to three-day) marinade. As Jonathan Kauffman explains in the Epicurious story linked above, it concentrates the flavors in those proteins, adding umami depth.

Sakai’s recipe for Koji-Marinated Salmon, which she calls her “‘no-recipe’ salmon dish,” proves the point; the extremely simple prep is a great one to add to your repertoire. See some nice fillets in the supermarket? Slap that shio koji all over them and figure out when you’ll eat them later. After overnight koji marination, give the fillets a quick wipe, run them under the broiler and dinner’s ready in less than minutes. While the salmon’s broiling, you can grate some daikon and ginger, which make a really nice garnish.

Koji-Marinated Salmon with grated daikon and ginger

Looking for dishes to round out the Koji-Marinated Salmon? Sakai’s “Potato Salada” (as it is called in Japanese) is wonderful, with lots of cucumber along with carrot and green beans. (And we have other dishes in our new Japanese section — check out the Spinach with Sesame Dressing.)

To make the Potato Salada, Sakai has you whip up some Japanese mayo and nerigoma (Japanese tahini). Our adaptation includes those instructions, but also provides a hack using store-bought mayo and tahini. (We hope Ms. Sakai doesn’t object — it was pretty good!)

I have not yet had a chance to make any of the noodles in the book, but the chapter is enticing, with beautifully photographed recipes showing how to make handmade soba, udon and ramen. Sakai, who was born in New York and grew up in Japan, Mexico and California, lives in Southern California, where she gives cooking classes — including very popular classes on soba-making. So this is definitely something I’ll want to explore. There are also recipes for tofu and miso (which takes from six months to a year and a half to ferment!), and for mochi. A pandemic’s worth of projects!

Meanwhile, what she writes about rice is illuminating. I’d been pulling my hair out during the pandemic because I couldn’t find sushi rice, and Thierry, Wylie and I were all craving sushi.

Sakai explains that any short-grain rice can be used for sushi — including Arborio, which I had in my pantry. I’d had no idea! I cooked that Arborio according to her instructions for Basic White Rice, and turned it into sushi rice, using her seasoning formula — 2 batches of basic white rice (about 8 cups) seasoned with 1/3 cup unseasoned rice vinegar, 3 tablespoons sugar and a tablespoon of sea salt. Perfect sushi rice! With it I made some simple maki rolls. We couldn’t have enjoyed it more.

With hardly an exception, the recipes in Japanese Home Cooking work perfectly — which is incredibly rare for any cookbook these days. I test-drove a lot of them (fifteen, at last count), and still have many on my can’t-wait-to-try list (Kombu-Cured Thai Snapper Sashimi, as soon as I can get my hands on some great fish, and Soba Salad with Kabocha Squash and Toasted Petpitas in the fall!).

Honestly, this is one of the best new cookbooks to come along in years. The writing throughout is clear, charming, thoughtful and frequently illuminating, and Poon’s photos are gorgeous. Already it has given me the tools to feel like a pretty confident Japanese cook, which is quite a gift indeed.

Japanese Home Cooking: Simple Meals, Authentic Flavors by Sonoko Sakai. Photographs by Rick Poon. Roost Books, 300 pages, $40.