By Leslie Brenner

One of the best things I’ve made from Emiko Davies’ charming new book, Gohan: Everyday Japanese Cooking, is what she calls Chilled Dressed Tofu.

It’s a block of tofu dressed as her obaachan (grandmother) used to prepare it for her: with soy sauce, sliced scallions, grated ginger and katsuobushi (shaved bonito). Her innovations are setting it on a shiso leaf, and adding a drizzle of sesame oil. No cooking required. Does it sound simple? It’s spectacular!

It comes together in a flash; really the only work involved is grating a piece of ginger and slicing a scallion. If you have access to a good Japanese supermarket, you should have no trouble finding fresh shiso leaves. But even if you leave off the shiso, the dish is really a treat — unexpectedly sumptuous and luxurious.

Silken (or soft) tofu is nicest for this dish, giving it a custardy, slippery texture. You could also use medium.

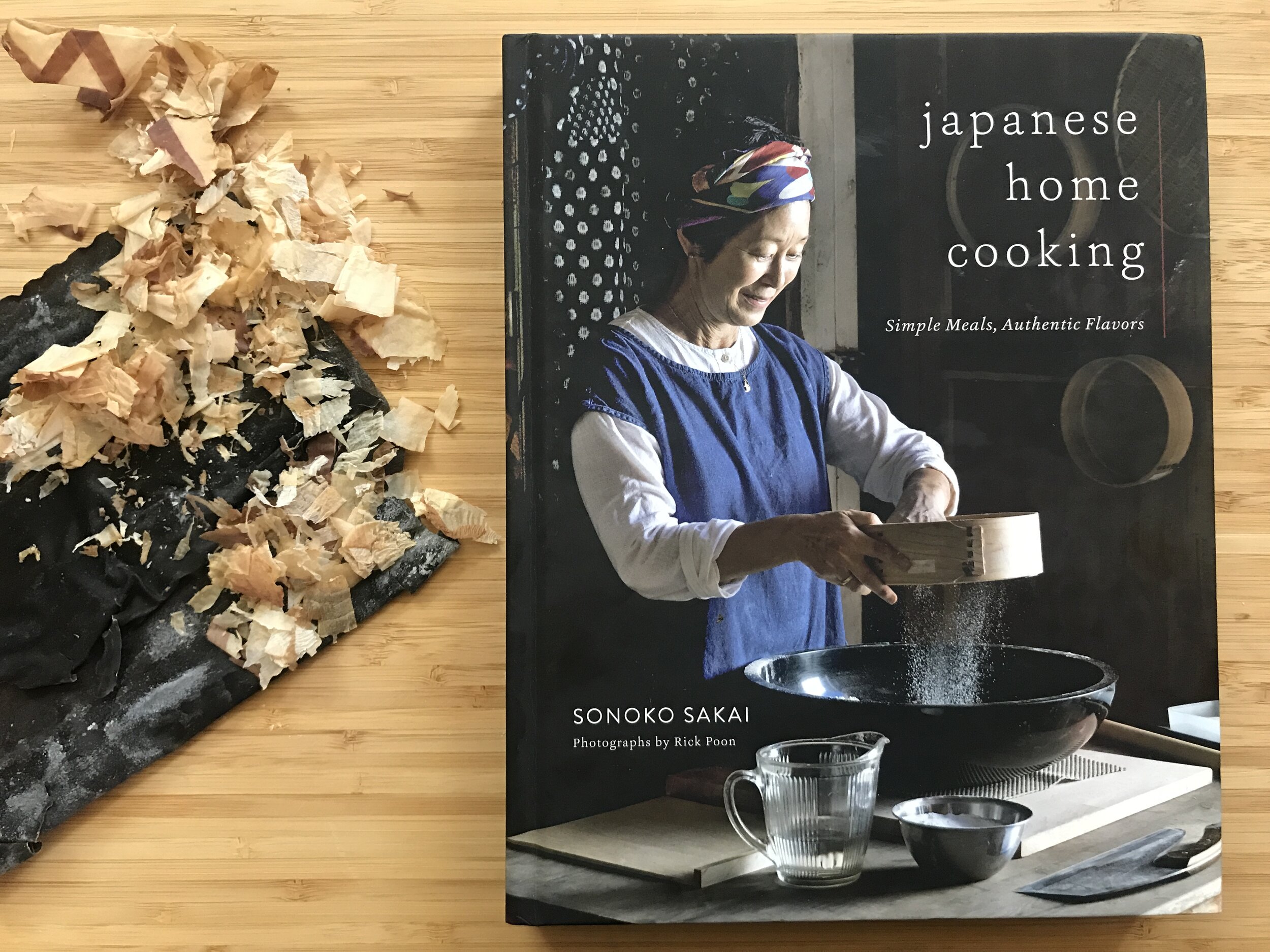

For the katsuobushi, any kind you find or have on hand will be fine; the fresher, the better. But if you’d like to make it really special, buy the most premium bonito flakes you can find.

READ: Katsuobushi (bonito flakes) will put a spring in your step and umami on your plate

Premium katsuobushi — dried bonito flakes — can be found at well stocked Japanese markets.

Best of all, if you prepare Japanese food with any kind of frequency, you may well have all the ingredients at hand (except probably the shiso). When the craving strikes, you’re just five minutes away from the treat.