By Leslie Brenner

A chill winter day is the perfect opportunity to make coq au vin — chicken marinated overnight and then braised in red wine and aromatics. Not only is the classic French dish fabulously delicious, it feeds a crowd (or lasts a few days into the workweek), and it will fill your living space with gorgeous aromas.

Seems like I’m not the only one craving this type of old-fashioned French comfort food; it’s having something that feels much bigger than a moment. A few days ago, The New York Times published a story about 25 essential dishes to eat in Paris. (The only one I’ve had is the first on the list — cassoulet from L'Assiette — and I couldn’t agree more. Go eat it, if you can!) Classic-style French bistros and brasseries are drawing crowds in Los Angeles, New York (always!), Chicago, Washington, D.C., Philadelphia, Dallas — and every other American city with a heartbeat. Buvette — which chef Jody Adams opened in New York a dozen years ago — now also has locations in Tokyo, Seoul and Mexico City (as well as Paris and London).

Oddly, for many crave-able bistro and French-home-cooking dishes, it’s not easy to find outstanding, workable recipes. For coq au vin, I’ve used (or consulted) probably no fewer than 20 recipes from various usually-excellent sources. (The great Julia Child fell down on this one; the coq au vin recipe in her Volume I of Mastering the Art does not have you marinate the chicken in the wine first; you merely braise it.)

The marinade: Start with a bottle of red wine.

For well over a decade, I’ve been working on my own recipe, informed by everything I’ve learned along the way. At long last I feel it’s worth sharing.

Developing it has required some accommodations. For one thing, traditionally the dish is made with a big old rooster — that’s the coq. These days, both stateside and in France, coq au vin is usually made with chicken. Either way, the bird is cut up, marinated in red wine and aromatics overnight (or up to two or even three days), browned then braised in the marinade and and garnished with mushrooms, pearl onions and lardons.

No problem with the mushrooms; you can use either white mushrooms or crimini. And you know what? I find the mushrooms so delicious in coq au vin that I’ve doubled the amount most recipes use — that way each person gets a generous amount.

Lardons, however, may be problematic for many American cooks, as it has become difficult to find the required slab (unsliced) bacon in supermakets, even the best ones — at least where I live, in Dallas, Texas. (Readers in better-provisioned cities like New York, L.A. and San Francisco may have an easier time.) Happily, we do have an old-school butcher shop that carries it; perhaps you do, too.

Pearl onions are another problem. No so long ago, I used to find them, or cippolini, fresh at our better supermarkets; alas, no longer. You can buy a bag of frozen pearl onions from Birds Eye or at Trader Joe’s — already peeled, which is nice, but they’re pretty flavorless. I’ve taken to hunting down the smallest shallots I can find and treating them like baby onions; sometimes it means pulling two or more cloves apart from a larger one. To tell the truth, the shallots add such nice flavor I actually prefer them to baby onions. If one day I can’t find small enough shallots, I don’t know; I’ll probably punt and use the frozen pearl onions. Or relocate.

In place of an old rooster, I had been using a whole cut-up chicken, but because it’s smaller than a coq, I added a couple of extra thighs or drumsticks. Who wants to go to all this trouble for just four servings? Lately, I started using only thighs and drumsticks — and why not? Everyone in my orbit prefers dark meat, and dark-meat only simplifies the preparation. (Though our recipe allows for either approach.)

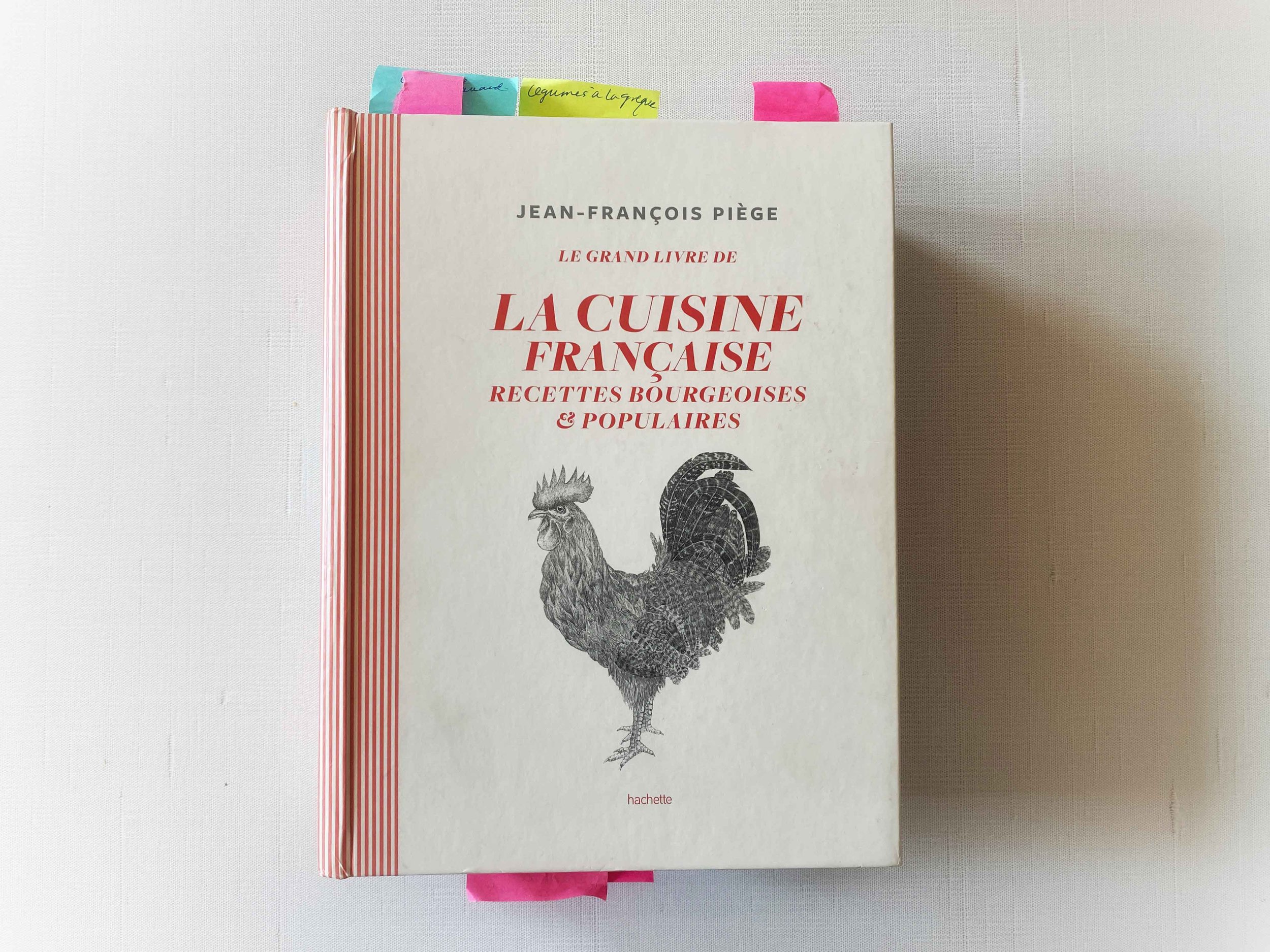

The versions of coq au vin that most informed mine are Anne Willan’s, from her wonderful 2007 book The Country Cooking of France, and one from Le Grand Livre de La Cuisine Française. Published (in French only) in late 2020, the latter book — which clocks in at 1,148 pages and weighs more than 8 pounds — comes from Jean-François Piège, one of France’s most renowned chefs. His book is an instant classic. I’ve cooked from it quite a bit (and referred to constantly) since the French cooking spree I’ve been on since I first lugged it back in my carry-on two years ago, having picked it up in a bookstore in Bordeaux. Imagine me literally running — with that anvil of a volume in tow — in order to make my connection (barely!) in Paris at Charles de Gaulle to come back home.

Piège’s and Willan’s recipes have much in common, but like many of the recipes in Piège’s tome, his is very restaurant-y. For instance, the chef assumes we will have on hand a liter of brown veal stock, 10 cl of sang de volaille ou de porc (poultry or pork blood), and some marc de Bourgogne (an eau de vie made from Burgundy grape must, like a French grappa) with which he wants us to flambé the bird first, and the garniture later. Oh, and that bird is either a coq or a Bresse chicken. He has us turn the mushrooms, sauté them in lardon fat and set them unsauced atop the finished dish, rather than cooking them in the sauce. Call me a peasant (or even a pheasant), but I like to simmer the mushrooms briefly in the sauce for a bit of flavor-exchange. (Willan’s recipe does that, but only for three to five minutes.)

One of the key issues with coq au vin is how to give the sauce enough body. Ideally, you’d use homemade chicken stock — that would have enough gelatin to give it a great texture. Most of us don’t have that lying around our freezer, though, so my recipe calls for store-bought chicken broth. Many recipes rely on whisking in beurre manié — softened butter mixed with flour — at the end. That works, but I don’t love its raw floury vibe; I’d rather leave the sauce a bit thinner and sop it up with lots of great crusty country sourdough. Recently, I came around to the idea of including a small amount of optional purchased veal demi-glace, which you can find in the freezer section of better supermarkets (or online at D’Artagnan). It’s expensive, but you can freeze and keep what you don’t use, and it does add silkiness and a bit more depth.

The wine question

I know what you’re wondering: What kind of wine should I use? First, don’t spend too much — pick up a bottle to cook with for $10 or less, if you can. Pinot noir, Beaujolais, Dolcetto d’Alba, Barbera, Sangiovese and Tempranillo are all good choices. Spend more, if you’re so inclined, on a great bottle to drink with it.

Besides the crusty bread, coq au vin is traditionally served with boiled potatoes tossed in butter and parsley, or maybe less frequently, pommes purées — mashed potatoes. I have also seen references to buttered noodles, which I have served chez nous. That raised an eyebrow on the face of the Frenchman to whom I am married, but all was forgiven once he dove into the saucy, fragrant, flavorful dish.

Don’t forget that you do need to start this dish the day before you want to serve it. The marinade needs to cool down completely before you add the chicken, so best to achieve that in the morning (it’s just 10 minutes or so of active time). Cool it down during the day, and plop in the chicken that evening. The next day, you’ll be ready to roll, whenever. Want to make the whole thing in advance? It’s even better, reheated, the next day.

I hope you enjoy this dish half as much as I do.

If you like this story, we think you’ll enjoy:

READ: Rich and soulful, beef bourguignon is always in style

READ: Easy, fabulous and just a little bit boozy, say ‘bonjour’ to Apple Calvados Cake

READ: Chef Daniel Boulud gives a humble French dish, hachis Parmentier, the royal treatment

READ To make a traditional gratin dauphinois, step away from the cheese

RECIPE: Café Boulud Short Ribs with Celery Duo

RECIPE: Céleri Rémoulade

ALL COOKS WITHOUT BORDERS FRENCH RECIPES