I went back and reread the headnote. The dish was traditionally made during olive-oil pressing season to celebrate the freshly-pressed oil, but now it’s enjoyed year-round. “Growing up, Sami ate it once a week,” goes the headnote. “It’s a dish to eat with your hands and with your friends, served from one pot or plate, for everyone to then tear at some of the bread and spoon on the chicken and topping for themselves.”

Traditionally, taboon bread is used in the dish. Baked on pebbles in a conical oven, the bread has a pock-marked surface that are great for catching the juices. But the recipe calls for any Arabic flatbread (we used pita from a local Lebanese bakery that I’d stashed in the freezer), or naan.

I can see why Tamimi’s mom, Na’ama, made it once a week: It’s fun and easy to make, probably no more than an hour from start to finish, and a great crowd-pleaser. I’ll be buying sumac futures this week: A full three tablespoons of the spice (a powerful anti-oxidant) go into the dish.

If you’re not familiar with Tamimi, some context may be helpful. Chances are you do know of Yotam Ottolenghi and his cookbooks. Tamimi is head chef for and a founding partner in Ottolenghi’s namesake London restaurant empire. He co-authored Ottolenghi’s first cookbook (Ottolenghi: the Cookbook, 2008). Together the two — led by Ottolenghi — created a style of produce-forward, Levant-accented, slouchy-chic improvisational cooking. In other words, what they did powerfully influenced the way so many of us cook now, and the way food looks on blogs and on Instagram — seductively dissheveled, vegetable happy and casually strewn with tons of herbs.

The two chefs went on to co-author Jerusalem: a Cookbook (2012). Both had grown up in Jerusalem in the 70s and 80s — Ottolenghi, who is Israeli and Italian, in the Jewish west part of the city and Tamimi, who is Palestinian, in the Muslim east. They didn’t know each other back home; they met in London, where they were both living in the 1990s. To the Jerusalem project, each brought his delicious perspective, and they wove together a gorgeous, deep, inspired, cookable portrait of their hometown. The book didn’t shy away from politics, but its explorations managed to unify rather than divide.

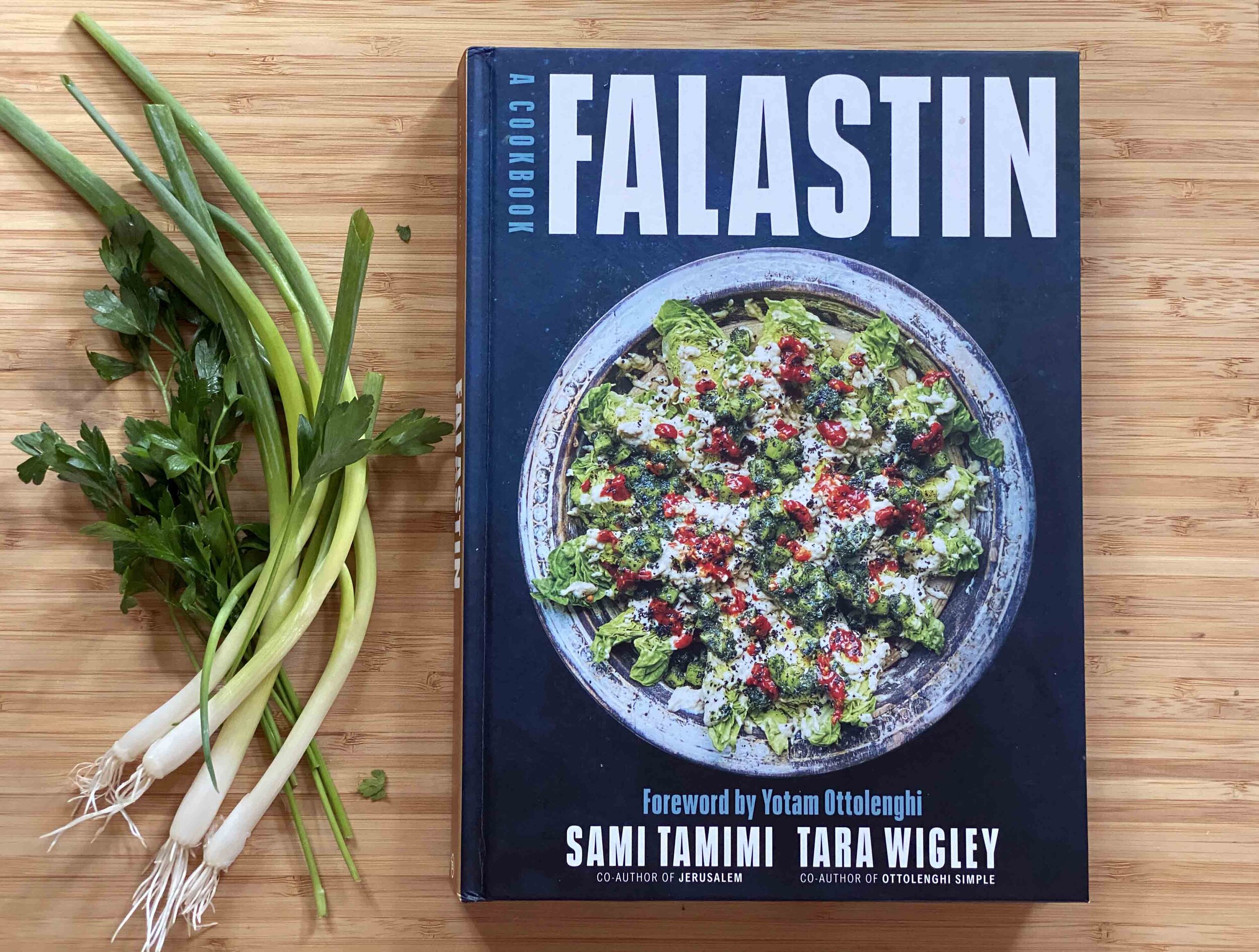

With Falastin, Tamimi explores the cooking of his beloved Palestine. “There is no letter ‘P’ in the Arabic language,” begins the introduction, so ‘Falastin’ is, on the one hand, simply the way ‘Falastinians’ refer to themselves.’”

Of course there is an “on the other hand” — and that’s the substance of the book, which Tamimi co-authored with Tara Wigley, a cook and writer who also co-authored Ottolenghi’s most recent book, Ottolengi Simple, and who is an integral part of the Ottolenghi family.