Fresh Herb Kuku, from a recipe in ‘Food of Life’ by Najmieh Batmanglij

By Leslie Brenner

How delightful to be turning to spring, which begins Monday. Celebrated by people in and from Iran, Nowruz — a two-week festival with Zorastrian roots, marking the season’s return — begins on the vernal equinox. Nowruz (also spelled Norooz), which means “new day,” is also celebrated by people in Iraq, Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and other cultures in the region.

Traditionally, it’s a time of feasting and rejoicing. This year, however, is bound to be a difficult one in Iran, due to the severe repression of and violence against women and the resulting protests. One can only imagine the battered population there wishing for a true new day.

Here, stateside, Iranian families will be cooking traditional foods or enjoying them in restaurants. Persian eateries in Los Angeles are offering solace to Iranians living there; L.A. holds the largest Iranian population outside of Tehran. Should you choose to cook to mark the holiday — whether you’re Iranian or cooking in solidarity with the women of Iran — we’re here to help.

There’s a wonderful primer about the Nowruz festival in Food of Life, Najmieh Batmanglij’s encyclopedic book subtitled “Ancient Persian and Modern Iranian Cooking and Ceremonies.”

In every household, Batmanglij explains, a special cover is spread on a carpet or table — the sofreh-ye haft-sinn, or “seven dishes” setting. Each dish served begins with the Persian letter sinn, and they represent, respectively, rebirth, health, happiness, prosperity, joy, patience and beauty. Now that’s a lot to celebrate!

“The traditional menu for the Nowruz gathering on the day of the equinox usually includes fish and noodles,” Batmanglij writes. “It is believed they bring good luck, fertility and prosperity in the year that lies ahead.”

Batmanglij’s Menu:

• Noodle Soup (osh-e reshteh or ash-e-reshteh). Noodles, she writes, “represent the Gordian knots of life. Eating them symbolically unravels life’s knotty problems in the coming year.”

• Rice with Fresh Herbs and Fish (Sabzi polow ba mahi). Herb rice represents rebirth and fish represents Anahita, an angel of water and fertility.

• Herb Kuku. The eggs and loads of fresh herbs in this frittata-like dish represent fertility and rebirth.

• Sabzi Khordan with Bread. Iran’s ubiquitous herb platter with cheese and nan-e barbari (flatbread) represents prosperity.

• Wheat Sprout Pudding. For fertility and rebirth.

• Sprout Cookies. Prosperity and fertility.

• Seven Desserts. Representing nourishment, light, love, sweetness and prosperity.

Three great dishes to make

Sabzi Khordan — an Iranian herb platter — is a must at Nowruz celebrations (and every other Persian meal!).

Sabzi Khordan with Cheese and Nan-e Barbari

We’re leading off with the herb platter known as sabzi khordan, as it’s such an essential part of the Iranian table – not just during festivals, but every other day, as well. “It’s essential to any meal we have, always,” says Nilou Motamed. The food-world celeb — a permanent judge for Netfix’s “Iron Chef” revival and my editor long ago at Travel + Leisure — is a native of Iran.

Putting together the platter itself requires no cooking, just collecting, washing, trimming and assembling herbs, scallions, cukes and radishes, and sourcing the best feta you can find (Bulgarian, if possible). Toasted walnuts are optional. Nibble all of it to your heart’s delight before, during, and in-between everything else.

With it you’ll want the flatbread known as nan-e barbari. Making one is easier than you might think, thanks to a hack Nilou gave us when I interviewed her a few years ago for a story about sabzi khordan: Her mom uses frozen pizza dough. It’s super fun and easy to make. Flatbread in hand, you can create the perfect bite — what Nilou calls a loghme. “You put some feta cheese in the bread, and then whatever your perfect complement of herbs is — whether you’re a dill or a tarragon person, or you like both, maybe the little tail of a scallion.”

New Year’s Bean Soup (Ash-e-Reshteh)

This vegetarian bean soup, chock full of herbs and other greens, stars those long soup noodles (known as “reshteh”) that will untangle life’s problems You can make them by hand; Naomi Duguid gives instructions for doing so in her gorgeous book, Taste of Persia, from which our recipe is adapted. You can also buy them in Middle Eastern groceries carrying Iranian ingredients, buy them online, or substitute dried linguine — which many recipes, including Duguid’s suggest. Another Iranian ingredient, kashk — a fermented milk product made from whey — may also be found in Middle Eastern groceries; it’s optional in Duguid’s version, and the soup is delicious even without it.

We featured the recipe a few years ago in a short piece about Persian New Year’s bean soup.

RECIPE: ‘Taste of Persia’ Ash-e-Reshteh (New Year’s Bean Soup)

Fresh Herb Kuku

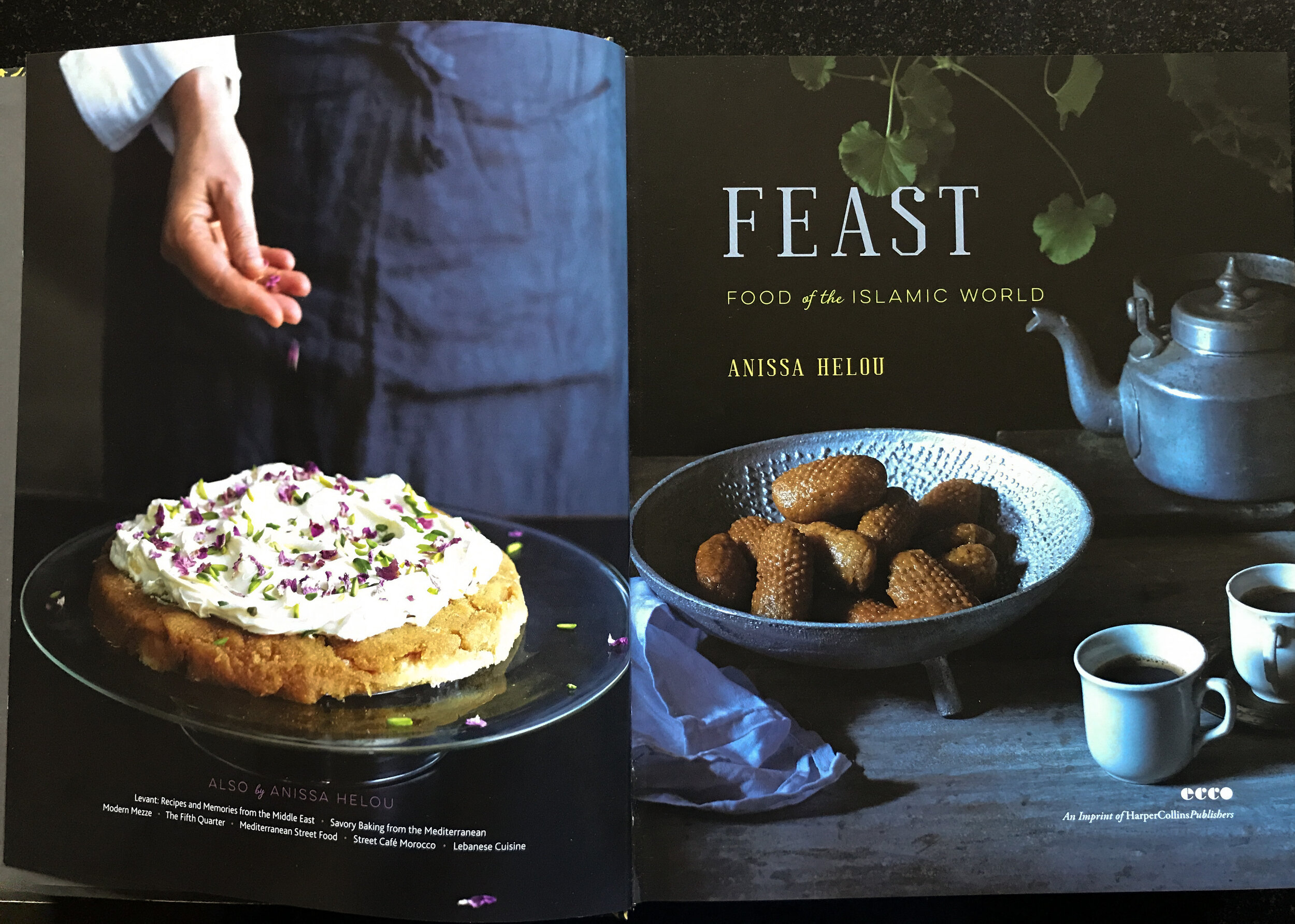

Finally, there’s the glorious frittata-like egg-and-herb kuku (shown at the top of the story). To make it, season beaten eggs with turmeric and advieh — a fragrant mix of ground dried rose petals, cinnamon, cumin and cardamom. (Cooking Iranian food is always a delightful to the senses.) Add a ton of finely of herbs (parsley, cilantro, dill and fenugreek) and lettuce, plus garlic, scallion, chopped walnuts and sautéed chopped onion. Pour the batter into a skillet in which you’ve heated oil, butter or ghee, cook it slowly until it has set in the center, then finish it quickly under the broiler. Top it with caramelized barberries.

RECIPE: Najmieh Batmanglij’s Fresh Herb Kuku

Here’s hoping for that true new day.