By Leslie Brenner

I don’t have much of a sweet tooth. But I do love to treat myself, now and again (and again and again!) to a slice of cake for breakfast. Or with a cup of tea in the afternoon. I love any dessert involving lemons, and I’m a pushover for almond cakes. Blueberries? Can’t get enough of ‘em.

Show me a gorgeous photo of a blueberry, almond and lemon cake, and that plan I had for shedding those extra Covid 19 pounds (yes literally 19, sorry to say) goes straight out the window.

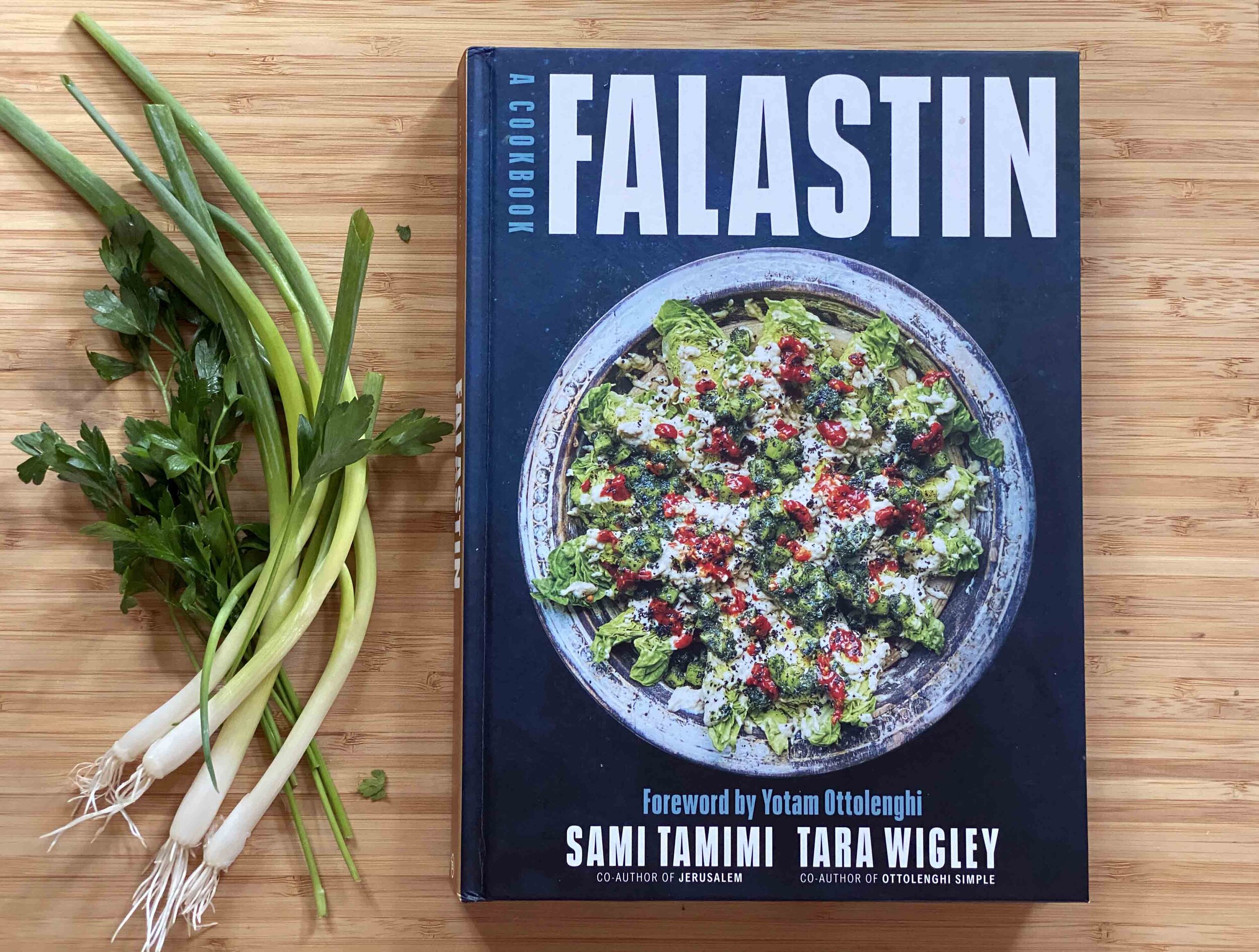

There it was, on page 277 of Ottolenghi Simple, nestled seductively on brown parchment, its top looking like woodland berries nestled in a blanket of icing-snow. I had to have it. I couldn’t even wait for the right ingredients: Lacking fresh blueberries, I used a pack of frozen “wild” ones I’d been stashing just in case of this kind of emergency.

The Ottolenghi cake was very, very good. So good, I had to make it again — this time with fresh blueberries, which I knew would give it more juicy, bright pop. As Ottolenghi intended.

But being that person who is not exactly a sweet tooth, I’d cut back the sugar a bit. And because I’d always rather eat whole grains than white flour, I’d try making a swap. I wasn’t sure whether whole wheat flour would be odd with the almond meal that made this an almond cake, but it wouldn’t hurt to try. And because I love citrus, I’d make it more lemony — adding more zest and juice to the batter, and more juice to the icing.

I went for it — not revealing my nefarious, health-conscious tweaks to the rest of my household, two of whom are sugar-loving dessert-maniacs.

They loved it! No one noticed the whole-wheat flour or the missing quarter-cup of sugar. The texture was even nicer, and the extra blueberries I threw in were a bonanza.

The top lost its snowy look, a casualty of the added lemon juice, which turned the icing into more of a glaze — but I preferred it this way.

Especially because of this: Now we had a cake that didn’t look so much like a dessert. I could eat it for breakfast! I could eat it after lunch! I could eat it with tea, or with coffee, in the afternoon!

Say hello (and then goodbye!) to the Blueberry-Lemon-Almond Anytime Cake.